[ad_1]

In 1925, Harold Stanley Ede (1895-1990), renamed Jim by his spouse Helen, was a junior curator at what was then known as the Nationwide Gallery of British Artwork, now Tate Britain. Ede, an alumnus of Newlyn Faculty of Artwork and the Slade in London, didn’t flourish amongst all of the mandarins and Widmerpools alongside whom he initially discovered himself working. However there have been consolations: with some assist from his father, a Cambridge-educated solicitor, he was in a position to purchase a Georgian city home in Hampstead. Then, in 1926, a pile of works by and paperwork concerning the French artist Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891-1915)—the artist added the Polish surname of his girlfriend Sophie Brzeska to his natal one; Laura Freeman right here considerably snippily excises it—was “dumped” within the gallery’s boardroom, which Ede was utilizing as an workplace. A coup de foudre ensued; a portion of this materials was acquired, someway or different, by Ede, and a brand new life started.

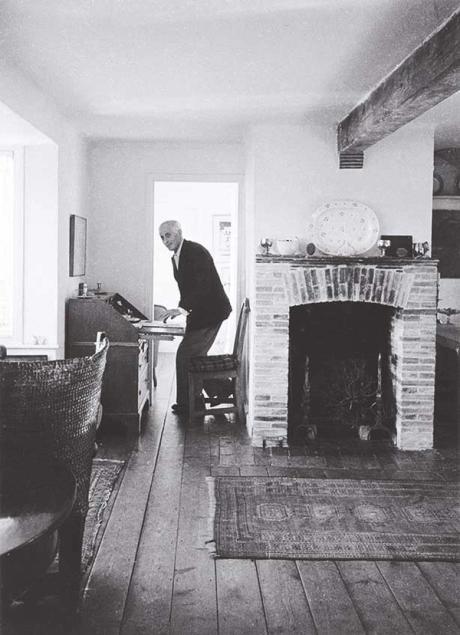

Ede utilized his formidable energies to constructing a contract profession: essays, critiques, lectures and his 1930 guide on Gaudier-Brzeska, Savage Messiah. He toured the US, making an attempt towards the percentages to sound the trumpet for British artists of the interval, corresponding to Ben and Winifred Nicholson, the nice Cornish naive painter Alfred Wallis, Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore. He constructed a home in Tangier, Morocco, the place troopers had been invited for recuperation through the Second World Conflict. Lastly, within the Fifties got here Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, an try (maybe) to recreate the freewheeling “open home” Sundays he had hosted in Hampstead in his youth, the place artwork, music and different good issues may very well be loved and talked about in a home relatively than institutional setting.

Though Freeman, the chief artwork critic on the Instances, makes elegant use of works from Ede’s assortment to border and punctuate her account of his life, the first focus of the guide is on the friendships that he made and maintained through the years. Many individuals thus graced are well-known in their very own proper: not simply Ede’s steady of British artists however the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși, whose ramshackle studio compound in Paris could have influenced Ede’s determination to purchase a number of small buildings at Kettle’s Yard relatively than one huge one elsewhere, the psychologist Donald Winnicott, the Bloomsbury-ite Ottoline Morrell, the writer and adventurer T.E. Lawrence, the poet Kathleen Raine… an entire mid-century gossip column’s price. Paul Bowles, Truman Capote and Gore Vidal all got here to name in Morocco, and Daniel Barenboim and Jacqueline du Pré performed on the opening of the Kettle’s Yard extension in 1970. Ede had a small function in Ken Russell’s 1972 movie of Savage Messiah.

Amid the mêlée, the person himself doesn’t fairly come into focus. Freeman writes in a form of free oblique type, as if she is celebration to what’s going on inside her topic’s head at any given second, however—maybe out of courtesy—she just isn’t falling over herself to grapple with the numerous contradictions of his life: the gem-like flame of his ambition versus his chaotic, impulsive decision-making, poor book-keeping and illegible handwriting; his large, resourceful generosity in direction of his artist mates set towards the questionable ways—gazumping, gazundering, sock-puppet intermediaries and outright untruth—he deployed to accumulate this image or get that venture over the end line. He’s usually imagined to have been roughly chastely gay: Freeman suggests, slightly incuriously, that the “chaste” half could have stemmed from his devotion to his spouse, his worry of authorized penalties, a sure primness in direction of unorthodox life that he usually displayed, regardless of transferring in bohemian circles for a lot of his life, or the entire above. (She notes the pronounced asceticism and deepening spiritual perception of his later years, however it appears to not have occurred to her that there could have been a penitential ingredient to this.)

Ede’s most identifiable contribution to the best way we reside now could be arguably the “Kettle’s Yard aesthetic”, a palette of white partitions, Trendy artworks and objets trouvés (pinecones, pebbles, outdated bits of ironmongery) sparsely organized on good brown furnishings. It’s a look that itself accommodates a couple of contradictions: pious but whimsical, restrained but someway sensuous. Just like the Scandinavian design traditions with which it’s usually these days conflated within the dwelling areas of the bourgeoisie, it guarantees a way of life amongst lovely issues and giving due weight to their magnificence.

Keith Miller is an editor on the Telegraph and an everyday contributor tothe Literary Assessment and the Instances Literary SupplementLaura Freeman, Methods of Life: Jim Ede and the Kettle’s Yard Artists, Jonathan Cape, 400pp, 62 illustrations, £30 (hb), revealed 18 Might

[ad_2]

Source link