[ad_1]

Artists and designers at this time have an assortment of colors at their fingertips however entry to dyes has not at all times been so easy. Procuring and producing them has been fraught with hazards, from wrestling alligators in logwood mangroves to being punished by lack of limb in Thirteenth-century Italy for utilizing “knockoff” scarlet. A brand new e-book by the artist and designer Lauren MacDonald, In Pursuit of Coloration, brings collectively the historical past and origins of a few of the world’s most essential dyes. In neatly divided sections—alliteratively titled Flora, Fauna, Fungi and Fossil Fuels—MacDonald takes readers on a tour of the origins, myths and developments of various dyes, from the crushing of carnivorous sea snails to the synthesising of alizarin. Within the edited extracts beneath, we convey you a few of the vibrant tales behind the dyes.

The Bayer alizarin manufacturing facility in 1961 Courtesy of Bayer AG, Bayer Archives Leverkusen

Pliny’s putrid purple: murex

The origin story of murex purple dyeing has develop into the stuff of fantasy. In the future the Phoenician god Melqart was strolling alongside a seaside together with his canine. The canine ran forward, snuffling shells alongside the shore. Melqart known as to his canine, and it ran in direction of him, displaying a newly purple-stained nostril. Melqart thought the color was so lovely that he wished to make a tunic of the identical hue for his lover, the nymph Tyros. He set about scavenging for the ocean snails, and from these created probably the most vibrant dye the world had ever seen.

Monitoring murex purple’s real-world origins has confirmed difficult. The earliest proof of its use is from about 4,000 years in the past in Qatar. By the primary century AD there was such a thirst for purple that the writer and naval commander Pliny the Elder, whose recipe for making Tyrolian purple survives, dubbed the craze for the color purpurae insania—purple mania. Regardless of this, nevertheless, neither he nor different historical writers appear to have written correct directions for producing the dye. One archaeologist travelled to the Aegean Sea to attempt Pliny’s recipe for herself, and was dissatisfied by the drab grey-violets (and odious scent) that the dye pot produced.

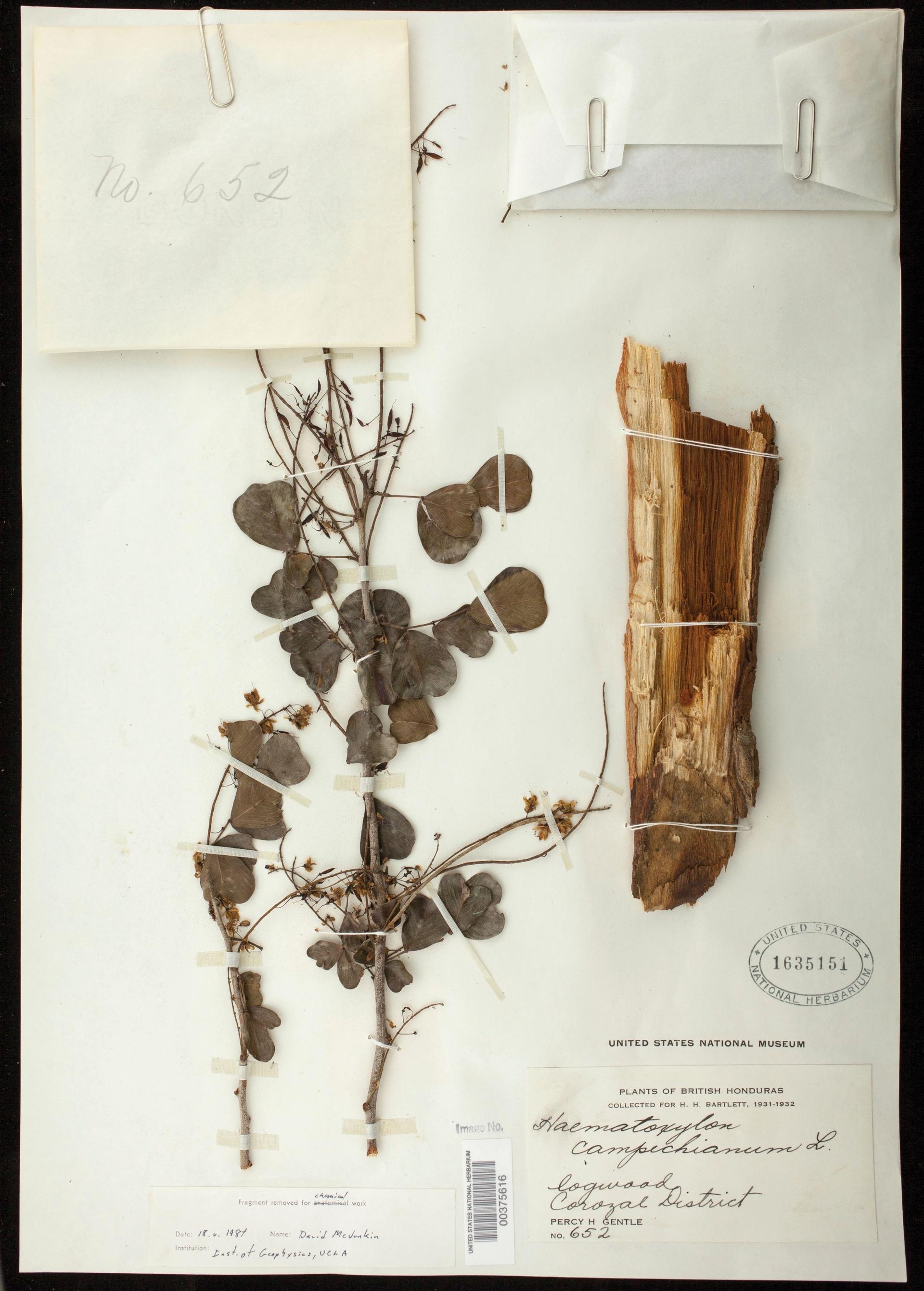

A logwood specimen Courtesy of the USA Nationwide Herbarium

Blackbeard ahoy: logwood

Logwood, used to make black dye, thrives within the watery panorama of mangroves and marshes alongside the coast of Mexico and South America. Its trunk is slim and crooked, and it has clusters of frothy, yellow blossoms. The wooden is each exhausting and heavy, and whereas the outer wooden is pale, logwood’s interior core is stained darkish reddish-brown, hinting at its potential as a dye. Indigenous civilisations used logwood for a number of millennia as a dye and as medication earlier than the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and his cronies confirmed up. Aztecs and Mayans handled varied illnesses with logwood, together with anaemia, dysentery, diarrhoea, tuberculosis, and menstrual cramps.

Logwood shortly gained recognition in Europe. At first Spain had a monopoly on the commerce, and the restricted provide meant logwood grew to become so worthwhile that it was topic to rampant piracy—primarily by the English. Throughout the reign of Henry VIII one shipload of logwood was value a yr’s commerce in every other cargo. In 1581, Queen Elizabeth I banned logwood importing and dyeing, blaming its poor lightfastness, however protectionist commerce coverage was the extra seemingly motivation for the ban. England had a flourishing woad business and logwood was a risk. By 1585, a tense commerce dispute between England and Spain erupted right into a decades-long commerce struggle, and logwood was one of many commodities at its centre. Breaking Spain’s monopoly was thought-about a key issue within the sinking of the Spanish Armada in 1588.

Yellow sub-aquamarine: weld

Weld’s superiority over different yellow dyes is for its fastness—its capacity to remain shiny and vibrant over time. Alongside woad and madder, it shaped the “grand teint”, the Medieval triad of quick, go-to primary-coloured dyes. And whereas weld is the quickest—or most everlasting—yellow, it’s acquired nothing on the permanence of blues and reds. There aren’t any naturally occurring yellow colourants which have the endurance of indigotin or alizarin. So, medieval tapestries usually get “the blues”, that means the sections that have been as soon as inexperienced flip aquamarine over time. These inexperienced sections have been normally dyed with woad and weld, and whereas the weld yellows fade over time, the woad blues stay, inflicting some medieval tapestries to appear to be they’re set underwater.

A Norwegian girl sporting a folks costume. Conventional Norwegianembroidery used wool dyed from Krapp (madder) Søstrene Persen, 1901. Courtesy of The Fallaize Assortment, Wellcome Assortment

Purple-faced treatment: madder

Nothing concerning the madder plant’s above-ground look signifies that it’s a dye plant. It’s a hardy herb that thrives in marshy, moist soil; its lemon-yellow (not purple) flowers are nestled amongst small, pointed leaves. However the lumpy orange-red roots of the dyer’s madder plant betray it as a supply of purple dye. Gnarled just like the fingers of a fairytale witch, the twisted roots might be stated to own a sort of colour-magic, producing a strikingly broad and various palette of reds.

Throughout its lengthy tenure as a dyestuff, madder has developed an affiliation with the navy, from the battle costume of the Romans to the English purple coats. In historical Greece, Spartans used to dye their garments purple to cover bloodstains, and Napoleon mandated its use throughout his officers’ uniforms. Rubia tinctorum has been used medicinally, too. One Sixteenth-century account recommends utilizing madder for bruises and wounds. The well-known English doctor Nicholas Culpeper prescribed its use for jaundice, palsy, sciatica, haemorrhoids, and eliminating freckles.

• Lauren MacDonald, In Pursuit of Coloration, From Fungi to Fossil Fuels: Uncovering the Origins of the World’s Most Well-known Dyes, Atelier Éditions & D.A.P., 272pp, £37.50 (hb)

[ad_2]

Source link